Synthesis: A semester in review

- Tracey DaSilva

- Mar 30, 2021

- 10 min read

Updated: Apr 5, 2021

photo by: Alexander Himmeck

As this semester winds down to an end and I reflect upon what I’ve learned and accomplished throughout the duration of this course, I wish to summarize my blog posts and demonstrate how my discipline of mental health nursing is interwoven into every facet of Canadian health and healthcare. The five blog posts are as follows: 1) The meld of personal meets professional. Can they be the same; 2) Intellectual and developmental disabilities & oral hygiene; 3) The Canada Health Act, antiquated or as relevant as ever? 4) Seated at an empty table: food insecurity and Covid-19; and 5) Rising from the ashes: Covid-19 and the resiliency of nurses.

1) The meld of personal meets professional. Can they be the same?

Our semester began with the daunting task of developing an online professional presence and to take stock of our existing personal and professional identities and consider how they may be improved upon in a professional and social media audit. These audits would later inform the mainstay of our primary objective, which was to curate a professional ePortfolio. In one of my first blog posts for the course and subsequent first blog, I shared that as a registered nurse (RN), I am a self-regulating professional, as identified in the Regulated Health Professions Act, 1991 and in the Nursing Act, 1991. I am fundamentally held to a higher standard than other members of the public. When considering what my professional identity should include, I explored my regulatory body, the College of Nurses of Ontario (CNO) along with one of my professional associations, the Registered Nurses of Ontario (RNAO) to acquire more knowledge about a professional online presence. The overarching message which was solidified what my classmates had already determined and expressed to me: that RN’s, as members of one of the most trusted professions, are indeed held to a higher standard by the public, and therefore an online presence must exude the very principles which are integral to the profession of nursing.

2) Intellectual and developmental disabilities & oral hygiene

We were encouraged to connect with a peer in another province and discipline, to discuss how our respective roles might interface the other. I partnered with Amelia, a registered dental hygienist in Nova Scotia as I proposed a scenario where we might overlap in our different roles. As an RN in Ontario, I shared of my experiences in working with individuals with an intellectual and developmental disability (IDD) and how their oral hygiene appeared to be lacking. In my professional experience, the completion of adequate oral hygiene as an activity of daily living (ADL) is heavily reliant upon having a care provider assist or totally complete this task as some individuals with IDD cannot appreciate the importance of this ADL. Unfortunately, in my practice, this seemed to fall by the wayside, most often due to aggressive behaviours (Chadwick, Chapman, & Davies, 2017). In my research, I found that individuals with IDD experience poorer oral and dental health, and are at an increased risk for developing complications such as aspiration pneumonia, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, respiratory disease, and even stroke. This can ultimately and negatively impact the individual’s physiological and social health, leading to toothache, oral pain, anxiety, and difficulty performing ADL’s (Wilson, Lin, Villarosa, Lewis, Philip, & Sumar, 2019).

My workplace has a dental clinic and will provide very basic cleaning, however if more treatment is required, the client must go to another hospital to receive the appropriate care. Amelia discussed how individuals with IDD can and are treated in the community clinic setting, but that they often require general anesthesia to receive comprehensive oral care and treatment as they are often unable to appreciate the reason for the dental appointment and procedure. furthermore, Amelia asserted that dental care has become more of a preventative approach, rather than a reactive one. With this, she also found that oral care is lacking in inpatient hospital units as oral care typically falls on the care provider or a family member who is visiting. The upshot of this revealed that individuals with IDD experience pooper overall health outcomes than those without IDD. But good oral health can be attained by providing supportive oral care, which include brushing teeth and facilitating routine dental checkups (ward, et al., 2019).

3) The Canada Health Act, antiquated or as relevant as ever?

The Canada Health Act (CHA) 1985, delineates that only medically necessary hospital and physician services are covered but universal health coverage in Canada. Arguments against the current CHA argue the definition for coverage is antiquated and therefore leaves gaps in service which Canadians experience when accessing health care. There is a call for expansion of the HCA to broaden what is medically necessary to include costly prescription drugs, diagnostic and imaging tests, mental health services outside of hospital settings, adequate home care, and dental care for all citizens (Flood & Thomas, 2016). From a mental health lens under the current CHA, is not deemed as medically necessary, despite an alarming 20% of Canadians will experience a mental health challenge at given time, and a subsequent 80% of Canadians will also experience the effects and impact of mental illness, in providing care for their loved ones (Chandler & Flood, 2016). In the present Covid-19 pandemic, it stands to reason that more Canadians will experience a mental health challenge in their lifetime. This highlights the concern that individuals who live with a mental illness, and their loved ones who provide care to them, experience a “fragmented system that does not meet their needs” (Chandler & Flood, 2016). The inherent consequences of this, is that Canadians may place their mental health challenges on the backburner due to inaccessibility and cost of prescribed medication (Canadian Civil Liberties Association, 2017).

4) Seated at an empty table: food insecurity and Covid-19

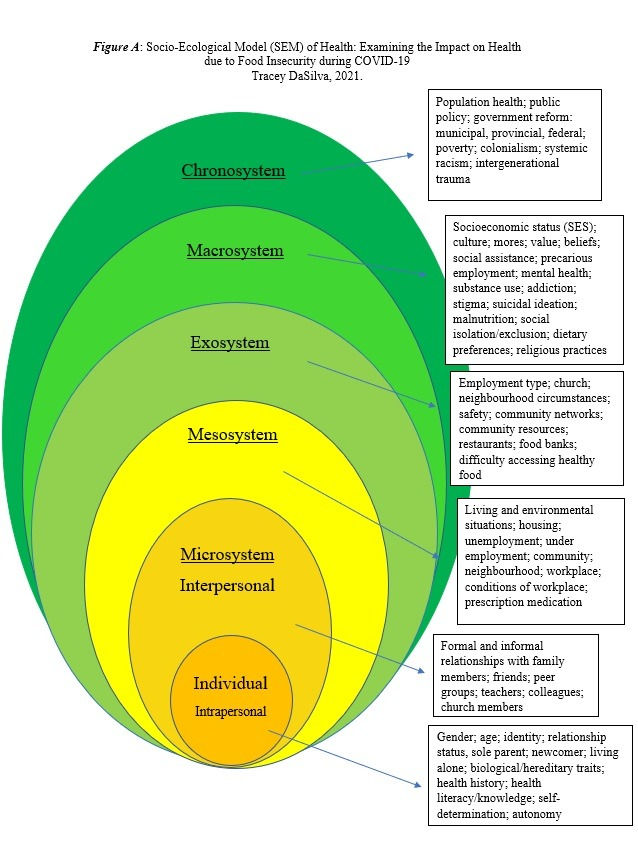

I utilized an adapted socioecological model (SEM) to apply a multilevel approach to the public health crisis and population health concern of 1 in every 7 Canadians who are experiencing food insecurity due to covid 19 (Polsky & Gilmour, 2020). Food insecurity occurs “whenever the availability of nutritionally adequate and safe food, or the ability to acquire foods in a socially acceptable way, is limited or uncertain” (Peng, Dernin, & Barry, 2018). Food security is a basic, fundamental human right (Food Secure Canada, 2020). I discovered that food insecurity affects vulnerable and marginalized individuals, particularly those who fall on the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum. Black Canadians, Indigenous Peoples and Persons of Color (BIPOC) (Canadian human rights commission, CHRC, n.d.), along with those who are precariously employed and housed, displaced persons, individuals with special needs/disability, aged individuals, immigrants, and those living with a mental health challenge (Ikura & Tepper, 2020).

To explain the SEM, I used the analogy of the Matryoshka dolls and how each one nests inside the other to build the multilevel system which includes the following spheres: individual, microsystem, mesosystem, Exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem. Please see Figure A below:

It comes at no surprise that food insecurity poses a dangerous risk to the health and wellbeing of an individual, and this is evident in all spheres of the SEM as the “impact of COVID-19 pandemic on food security and poor health outcomes is complex, multilevel and bidirectional” (Leddy et. al., 2020). In Canada, “household food insecurity is associated with heightened nutritional vulnerability, increased risk of numerous physical and mental health problems, higher mortality rates, and higher health care costs, independent of income, education, and other social determinants of health” (Tarasuk, St-Germain, & Mitchell, 2019). Furthermore, depression is linked to many risk factors in relation to food insecurity, including one’s socioeconomic status, their physical activity, health comorbidities, and genetic predispositions (Shafiee, Vatanparast, Janzen, Serahati, Keshavarz, Jandaghi, & Pahwa, 2021).

5) Rising from the ashes: Covid-19 and the resiliency of nurses

The influence of the Covid-19 pandemic is that is presents as an emerging health concern. We know the psychological burden of this pandemic will persist long after the pandemic has resolved. The impacts are and will continue to be pervasive, affecting each of us in a rippling effect, the ebb and flow of which will eventually shape a new semblance of normalcy (Hotopf, Bullmore, O’Connor, & Holmes, 2020). A year into the pandemic, the psychological effect has been devastating, and I would argue particularly more so for front line workers including nurses. Nurses are faced with fears and concerns of insufficient supply of personal protective equipment (PPE); inadequate staffing on shift; working long hours and overtime; isolation from loved ones at home and managing family responsibilities; concerns for patients’ wellbeing, and an increased risk of contracting Covid-19 themselves (Stelnicki, Carleton, & Reichert, 2020). Please see the diagram below by Crowe, et al., 2021) to illustrate the contributing factors to psychological distress.

How do we allay those fears for front line workers, specifically nurses? Firstly, but supporting nurses psychologically as this directly translates into safe and competent patient centred care. Recognizing that this will require a multilevel response with key components that will be required at different times (Mabel & Bridges, 2020). Additionally, Nelson and Lee-Win (2020) claim that healthcare facilities should enhance support through employee assistance programs (EAP), which enables healthcare workers to connect with mental health professionals for cost free services. This is an ethical reciprocity tenet, wherein, the nurse provides care to patients with Covid-19 or another emerging disease, and the hospital ensures that the healthcare provider has adequate access to appropriate PPE, and that they receive the necessary and individually specific level of support to maintain their wellbeing while caring for very ill individuals (Puradollah & Ghasempour, 2020).

This semester has proven a challenge, and one that I confidently felt up to the challenge for. I have learned about the Canada Health Act and its shortcomings. I better understand the social determinants of health and how they influence the health and wellbeing of individuals, families, and larger communities. I have a newfound appreciation for the tireless work from other healthcare professionals in differing disciplines. I have an enhanced understanding of how my role as a mental health registered nurse fits into the healthcare system and the emerging trends as we look to the future. I still declare that I am part of a very privileged profession, and as such, I am lucky to be completing this course and moving onto the next one in my academic journey.

References

Canadian Civil Liberties Association (CCLA). (2017, February 9). The current state of mental health in Canada. From https://ccla.org/current-state-mental-health-canada/

Canadian Human Rights Commission (CHRC). (n.d.). Statement – inequality amplified by COVID-19 crisis. From https://www.chrc-ccdp.gc.ca/eng/content/statement-inequality-amplified-covid-19-crisis

Canadian Legal Information Institute (CanLii). (2017, December 12). Canada Health Act, 1985. From https://canlii.ca/t/7vfb

Canadian Legal Information Institute (CanLii). (2017, December 31). Nursing Act, 1991. From https://canlii.ca/t/2t0

Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA). (n.d.). The relationship between mental health, mental illness, and chronic physical conditions. From https://ontario.cmha.ca/documents/the-relationship-between-mental-health-mental-illness-and-chronic-physical-conditions/

Chadwick, D., Chapman, M., & Daviss, G. (2017, October 17). Factors affecting access to daily oral and dental care among adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of applied research in intellectual disabilities. From https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12415

Chandler, J.A., & Flood, C.M. (2016). Law and mind: Mental health law and policy in Canada. LexisNexis Canada

College of Nurses of Ontario (CNO). (2020, October 2). About the college of nurses. From www.cno.org

Community Food Centres Canada (CFCC). (2020, September 29). Beyond hunger: the hidden impacts of food insecurity. From https://beyondhunger.ca

Crowe, S., Howard, A.F., Vanderspank-Wright, B., Gillis, P., McLeod, F., Penner, C., & Haljan, G. (2021). The effect of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Canadian critical care nurses providing care during the early phase pandemic: a mixed method study. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing, 63. From https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102999

Ejesiak, K., & Flynn-Burboe, M. (2005, May 8). Animal rights vs. Inuit rights. Boston Globe.

Flood, C.M., & Thomas, B.P. (2016). Modernizing the Canada Health Act, Dalhousie Law Journal, 39(2), 397-412

Government of Ontario. (2018, November 16). Regulated Health Professions Act, 1991. Ministry of Health and Long Term Care (MOHLTC). From https://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/hhrsd/about/rhpa.aspx

Government of Ontario. (2018, November 16). Regulated health professions. Ministry of Health and Long Term Care (MOHLTC). From https://health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/hhrsd/about/regulated_professions.aspx

Health Canada. (2005, May 16). Canada health act – Links to provincial and territorial health care web resources. From https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-care-system/canada-health-care-system-medicare/provincial-territorial-health-care-resources.html

Hotopf, M., Bullmore, E., O’Connor, R.C., & Holmes, E.A. (2020). The scope of mental health research during the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath. British Journal of Psychiatry, 217(4), 540-542. From https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.125

Ikura, S., & Tepper, J. (2020, May 25). Don’t ignore the other curves that need to be flattened- unemployment, food insecurity, poor mental health, and housing instability. Toronto Star, the web edition articles

Kerr, J. (2014, June 24). Greenpeace apology to Inuit for impacts of seal campaign. From https://www.greenpeace.org/canada/en/story/5473/greenpeace-apology-to-inuit-for-impacts-of-seal-campaign/

Kim, S.C., Quiban, C., Sloan, C., & Montejano, A. (2020). Predictors of poor mental health among nurses during COVID-19 pandemic. Nursing Open, 8(2), 900-907. From https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.697

Leddy, A.M., Weiser, S.D., Palar, K., & Seligman, H. (2020, August 7). A conceptual model understanding the rapid COVID-19 related increase in food insecurity and its impact on health and healthcare. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 112(5), 1162. From https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqaa226

Maben, J., & Bridges, J. (2020). COVID-19: Supporting nurses’ psychological and mental health. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(15/16), 2742-2750 from https://doi.org/ 10.1111/jocn.15307

Mikkonen, J., & Raphael, D. (2010). Social determinants of health: the Canadian facts. Toronto, Canada: York university of health policy and management. From https://www.thecanadianfacts.org/the_canadian_facts.pdf

Nelson, S.M., & Lee-Winn, A.E. (2020). The mental turmoil of hospital nurses in the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, research, practice, and policy, 12(s1), s126-s127. From https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000810

Peng, W., Dernini, S., & Berry, E.M. (2018). Coping with food insecurity using a sociotype ecological framework. Frontiers in nutrition, 5. From https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2018.00107

Polsky, J.Y. & Gilmour, H. (2020). Food insecurity and mental health during COVID-19 pandemic. Health reports, 31(12), 3-11. From https://doi.org/10.25318/82-003-x202001200001-eng

Puradollah, M., & Ghasempour, M. (2020). Necessity of attention to mental health of frontline nurses against COVID-19: A forgotten requirement. International Journal of Community Based Nursing and Midwifery, 8(3), 280-281

Randhawa, S. (2017, November 17). Animal rights activists, Inuit class over Canada’s Indigenous food traditions. Gulf News.

Registered Nurses Association of Ontario (RNAO). (n.d). Social media guidelines for nurses. From https://rnao.ca/news/socialmediaguideline

Rodrigues, M., Weiner, J.C., Stranges, S., Ryan, B.L., & Anderson, K.K. (2021). The risk of physical comorbidity in people with psychotic disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 140. From https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110315

Shafiee, M., Vatanparast, H., Janzen, B., Serahati, S., Keshavarz, P., Jandaghi, P., & Pahwa, P., (2021). Household food insecurity is associated with depressive symptoms in the Canadian adult population. Journal of affective disorders, 279, 563-571

Stelnicki, A.M., Carleton, R.N., & Reichert, C. (2020). Nurses’ mental health and well-being: COVID-19 impacts. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 52(3), 237-239. From https://doi.org/10.1177/0844562120931623

Tarasuk, V., St-Germain, A.A.F., & Mitchell, A., (2019). Geographic and socio-demographic predictors of household food insecurity in Canada. Biomed central public health, 19(1), 12. From https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6344-2

Thornton, J. (2019, September 12). Animal Rights, imperialism, and Indigenous hunting. Indian Country Today

Ward, L.M., Cooper, S.A., Hughes-McCormack, L., Macpherson, L., & Kinnear, D. (2019, May 23). Oral health of adults with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review. Journal of intellectual disability research. From https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12632

Wilson, N.J., Lin, Z., Villarosa, A., Lewis, P., Philip, P., Sumar, B., & George, A. (2019). Countering the poor oral health of people with intellectual and developmental disability: a scoping literature review. BMC public health, 19(1), 1530. From https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7863-1

Comments